PHOTO

He was a number ten in the era of the great number tens, when fantasy was in power and a shirt number was enough to measure talent. After Roberto Baggio, Alessandro Del Piero and Francesco Totti, Gianfranco Zola completes the four-man 'Hall of Fame of Italian Football' by making his triumphant entrance in the company of another number ten like Zinedine Zidane.

"The company is not bad," he began jokingly. "I am surprised and delighted to receive this recognition. At a time when strikers are a rare commodity in Italy, even attacking midfielders seem to be an endangered species". Mancini also attributed this lack of talent to the fact that children no longer play football in the streets: "Roberto is right. There was a time when players came from the street or the parish, I am among them. Playing in the street you get used to going outside the box, you are more creative, whereas in a youth sector you grow up in a more organised and structured environment. After the advent of Arrigo Sacchi in Italy there was more focus on schematic players than extrovert players, this brought benefits, but creativity was neglected. I experienced this when I went to play in England, where they worked much less on tactics but gave more space to improvisation, to dribbling, thus also favouring the rhythm and intensity of the game".

Football has changed, the playmaker behind the forwards seems to be outdated and even talent has had to move, often to the flanks: "Players with similar characteristics to mine such as Politano, Zaccagni or Verde are played today as outside players. The context has changed and they are called upon to develop different qualities. Others, like Pellegrini, play in midfield".

Zola's footballing fairytale began in Corrasi, in Oliena, a town of six thousand inhabitants a few kilometres from Nuoro. From there Nuorese, then the C2 with Torres: "I played as a forward and it is no coincidence that one of my best seasons was at Parma, when I played as a striker or, as we would say now, as a false nine. With Torres I started as a midfielder and it didn't go badly'. It became impossible not to notice the talent of that Sardinian boy who handled the ball with white gloves and, as often happens, Luciano Moggi sniffed out the deal. In 1989, Napoli bought him for 2 billion lire and Gianfranco immediately found a special admirer in Diego Armando Maradona. 'Diego and Careca arrived when preparation had already begun and so Massimo Mauro and I found more space. I was able to make a name for myself playing as a midfielder and as a centre forward'. Two precious goals also came for the winning of the second Scudetto: "I was lucky enough to experience that celebration in Naples, it was extraordinary. I would be extremely happy if the third Scudetto came, the people of Naples deserve it. I know how important it would be for them".

But in Spalletti's Napoli would Gianfranco Zola have a starting shirt? "Good question, everyone would struggle to play in this Napoli. I would have had to work hard, but maybe I would have earned a spot. When I see them play I think 'wow', how wonderful. Their strength is not only in individual class, but in the collective". Speaking of individuality, Osimhen and Kvaratskhelia deserve a special mention: "Kvara I didn't know, I have a very high opinion of him. He is a very technical player, but also a team man. He has a great personality and his was a crescendo, he never stopped. He reminds me of George Best".

After Maradona's departure, the number ten jersey fell on his shoulders, a very heavy inheritance for anyone, even for a boy with an assured future: 'Wearing it was very exciting, but it could also have been extremely dangerous. I was good at taking the responsibility off myself, knowing that it would have been impossible to compare myself to Diego. Diego was unique'.

In the summer of '93 the love story between Zola and Napoli came to an abrupt end and the fans felt betrayed: "It wasn't an easy decision, I was very attached to the team and the city. But the club had financial problems that year and, apart from me, Ferrara, Thern and Fonseca were sold". At Parma came the first two international trophies, a UEFA Cup and a UEFA Super Cup, but also the 6th place in the 1995 Ballon d'Or ranking: "It was a very strong team, which could have collected more in the league too".

In a career that has never been trivial, Gianfranco turns another page. And leaves Italy: 'Me, Vialli and Di Matteo made a brave decision, which turned out to be an extraordinary experience. We went against the tide because at the time Serie A was the best league. At Chelsea they immediately fell in love with Zola, who had fun on the pitch and enriched his trophy cabinet with a Cup Winners' Cup, two FA Cups, an English League Cup and the Charity Shield. From the goal at Wembley against England, the most symbolic among the ten (look at that...) scored in the national team, to the honour of Officer of the Order of the British Empire, 'Magic Box' discovers that he has a special feeling with the United Kingdom. And even with Gianluca Vialli a deep bond was born: 'Sometimes we had different visions, but we always approached each other with the utmost respect. We had a great relationship, with his values he was important for the whole team'. There was no lack of jokes: 'I was looking for a house, in the evening I didn't know where to go to eat. Gianluca took me to a Japanese restaurant and invited me to try wasabi. I put plenty on a slice of bread, I almost ended up in hospital...'.

It is almost time to hang up his boots, but before leaving the stage, Gianfranco gives himself one last theatrical coup. He returned to his homeland, Sardinia, and dragged Cagliari back to Serie A to the tune of goals, earning himself induction into another 'Hall of Fame', that of the red and blue club: "It was another anomalous decision to leave a team aiming to win the Champions League to go and play in Serie B. I dreamed of bringing the experience I had gained to Sardinia, it was a heartfelt choice that I have never regretted".

More troubled was his relationship with the national team (35 appearances and 10 goals), characterised by some joy, but also by many disappointments, from the missed penalty against Germany at EURO '96 to the exclusion from the call-up for the World Cup in France '98: 'I think I failed to give my all to the national team. I could have given much more, unfortunately emotion played a bad trick on me. I've always loved the Azzurri shirt and if I became a footballer I owe it to the victory in the '82 World Cup, it was there that I understood what I wanted to do when I grew up. At times I wasn't able to be cool enough, that was my limitation.

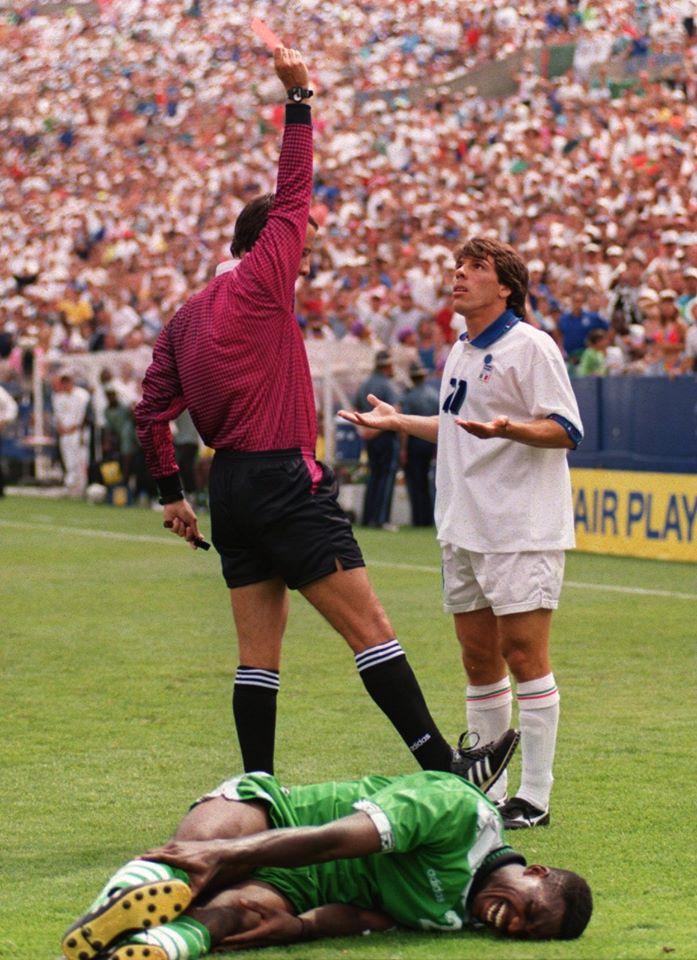

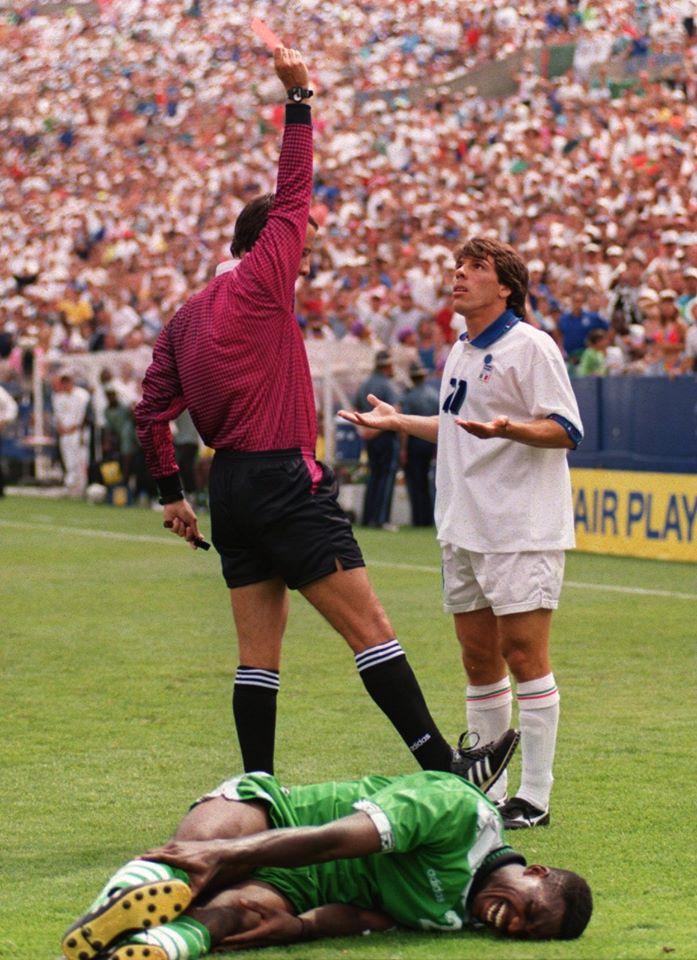

In the box of memories there is a special place for the goal that gave Italy the second success in its history at Wembley after the one signed by Fabio Capello in November '73 ('It was beautiful for me and for the many Italians who lived in England'). But it is impossible to forget one of the greatest injustices suffered by a national team player. If Arturo Brizio Carter does not have the same notoriety in Italy as Byron Moreno, it is only because Roberto Baggio's double against Nigeria saved Italy a resounding elimination in the Round of 16 of the American World Cup. The Mexican lawyer's name will forever remain etched in the mind of Zola, who was sent off for a non-existent foul twelve minutes after his entrance onto the pitch. The game was being played at Foxboro Stadium Boston, it was 5 July, and on that day Zola turned 28: 'It was without doubt the worst birthday of my life. I hadn't done anything, when I saw the red card I didn't want to believe my eyes'. The damage beyond the mockery was the two-day disqualification: 'A pity I didn't get more space, I felt I had a lot to give. And to think that in order to fly to the United States he had to beat off competition with a certain Roberto Mancini: 'We were in the running. Roberto was an extraordinary player, probably he too, like me, did not manage to show his full value in the national team'.

And perhaps it is no coincidence that Zola, like Mancini, wanted to rediscover the Azzurri shirt under a new guise, as assistant coach in Pierluigi Casiraghi's Under-21 team: 'It was a very nice time, I had a lot of fun. I had never thought of becoming a coach and that experience made me change my mind". The present sees him in a new role again, this time as vice-president of the Lega Pro led by Matteo Marani: "I had the good fortune to get to know, both as a player and as a coach, two different worlds like Italy and England. I'm not a politician, but a sportsman, and I hope I can make some useful suggestions". As always, tiptoeing in. But what feet...